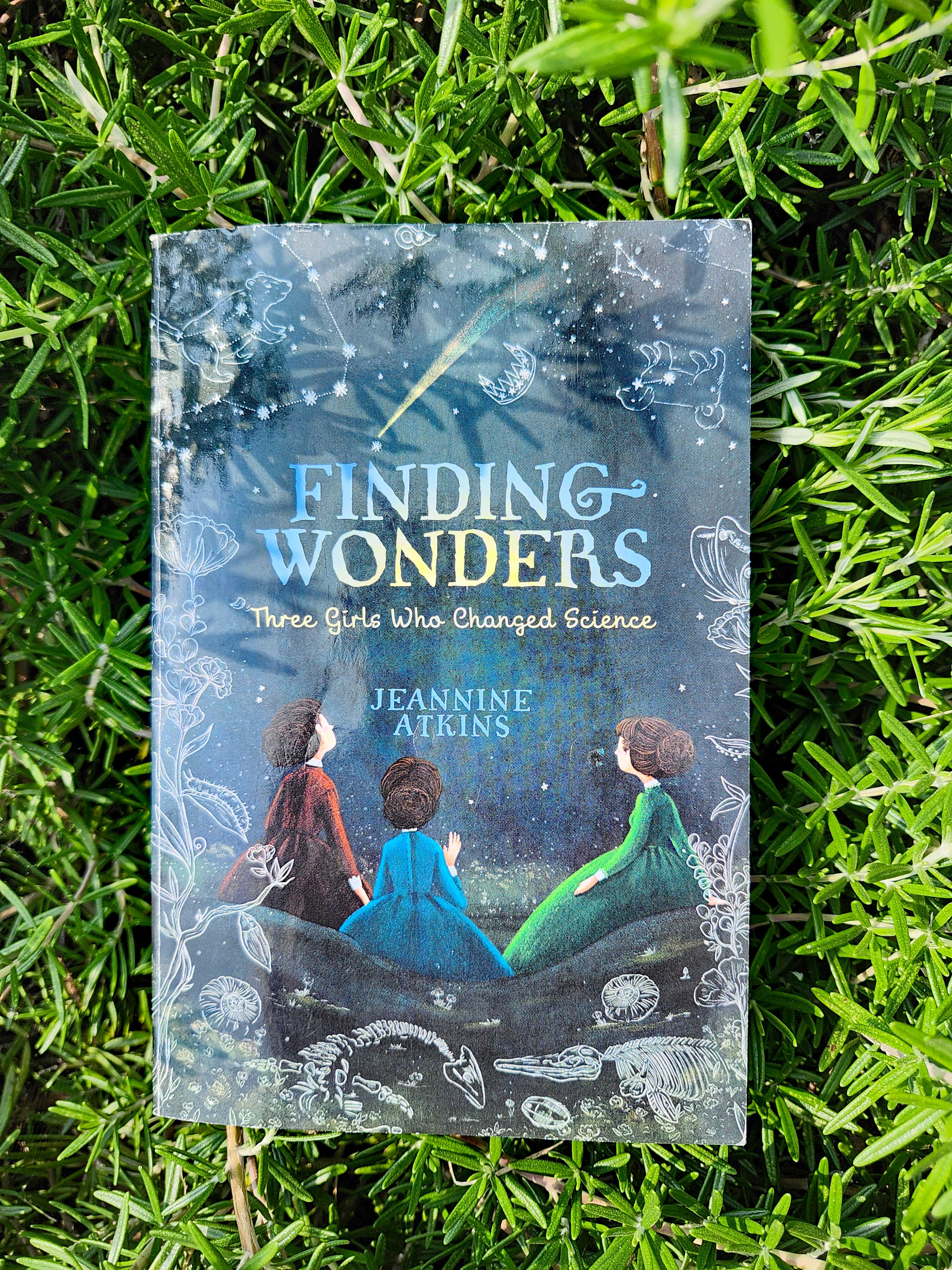

Atkins, Jeannine. (2016). Finding Wonders: Three Girls Who Changed Science. New York: Atheneum Books for Young Readers.

Sarah gifted me this book for Mother’s Day a few years back in what was undoubtedly a moment of book-fair delight. She knows my love for reading and sharing captivating children’s books. This gem is a collection of biographies written in verse about three remarkable women who revolutionized science: Maria Merian, Mary Anning, and Maria Mitchell. Their stories are a thrilling journey of discovery and innovation.

Maria Merian (1647-1717)

Maria Merian, a pioneer in biology, was the first to depict the life cycles of insects and their relationships with certain plants, contributing to the basis of ecology. Her work blended beautiful art and detailed information, a testament to her curiosity and the thrill of discovery. She defied the societal norms that confined women in the late 1600s, a testament to her courage and determination. Her unwavering perseverance and passion for her work elevated science to new heights.

I like this poem from Maria’s section, “What She Is Told.”

Women don’t cross the ocean,

at least not unless married to merchants or missionaries.

No one has sailed to another continent

just to look at and draw small animals and plants.

Some travel to claim land for kinds, find treasure like gold,

or collect bark, berries, and pods to spice cakes.

But no one has sailed from sheer curiosity about the world.

Mary Anning (1799-1847)

Almost a century later, we follow Mary Anning, who helped her father collect fossils from the cliffs near her home. She became a pioneering paleontologist and fossil collector through perseverance and passion. Her father was a furniture maker and an amateur fossil collector. He taught Mary how to look for fossils and how to clean them. On one of his fossil hunting trips, he was severely injured and could not work; already poor, their family slid further into debt. Mary persisted in her hunt for fossils, and her efforts were rewarded with a spectacular find. She sold this find and continued to uncover and sell fossils to support her work. She learned to read. In her way, she became a noted scholar. Her work, a testament to the power of perseverance, contributed to our knowledge of the Jurassic Age fossils and the age of the earth.

Here’s a lovely bit from Mary’s story in the poem “The Fossil Finder.”

As she looks for stones, scholars seek help from her,

although she left school when she was ten, about thirty years ago.

She hunts and chisels, but also reads complicated reports.

She Makes intricate drawings,

dissects squid and cuttlefish,

comparing their insides with feathery lines fanning

from what seems like spines on fossils of similar forms.

She weighs old theories, draws new conclusions.

Claiming this world, Mary claims herself.

Maria Mitchell (1818-1889)

Maria Mitchell was the only one of these three I had heard about. Since I am married to an amateur astronomer, her work came to my attention. Like Maria and Mary before her, Maria worked in the family business. Her father was a mapmaker and an educator. He charted the skies for the whaling ships of Nantucket, Massachusetts. Unlike the other two women, she was fortunate to be born to Quakers, who advocated equal education for girls. Maria went to school and was educated. She taught her father’s classes, opened a school, and advocated for more girls to be taught science and math. Although achievements by women were not plentiful, she did receive recognition and a prize for her discovery of what is known as Miss Mitchell’s comet (Comet 1847 VI).

From Maria’s section, I enjoyed this poem, “The Wider World.” It shows a bit of how she struggled even as a college professor.

Maria’s mother has died, but her father comes with her

to Vassar College, where he’s been given a room.

Maria sleeps on a cot under the observatory’s sky dome.

She likes using the tall telescope and teaching

young women, but she’s bothered by parents

who fret that advanced mathematics might strain

their daughters’ delicate constitutions.

She says, My mother had ten children

and did more night work than most astronomers. We’ll be fine.

In summary, this lovely book chronicles the perseverance and passions of these three scientists and celebrates their invaluable contributions to our collective understanding.